Next time: Carnegie Hall

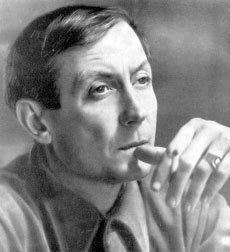

An encounter with the legendary Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Russia’s rebel hero, literary pop star and greatest living poet, at the conference celebrating the Centennial of the Nobel Peace Prize

The invitation came by email. I thought it was a joke. I mean, really, an invitation to represent England at the 100th Anniversary of the Nobel Peace Prize in Norway? Me? It also said I was to share a stage with Yevgeny Yevtushenko. Which sounded even more insane. I remember Yevtushenko from the 1960s when I was a university student in New York. He was the pop star of the intelligentsia in those days, everybody’s idea of a poet, passionate, courageous, glorious to look at. Women screamed and fainted at his performances.

People like me just don’t share stages with people like that. They don’t represent countries at Nobel Peace Prize Centenaries either.

This celebration was to feature seriously famous writers from all over the world, Gore Vidal, Andre Brink, Amos Oz as well as Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Count Nikolai Tolstoy, Tolstoy’s grand nephew. The Norwegian Nobel Institute and the Norwegian Ministry of Affairs had taken the conference title from Tolstoy’s War and Peace, which is why my novel Theory of War seemed to fit. I figured they hadn’t read the book. After all, it’s about a couple of guys who hate each other. War is only a metaphor in it.

Never mind. That was hardly a point for me to raise. I accepted the invitation. Of course I did.

The conference took place in September of 2001 in Tromsø, high up above the Arctic Circle, a pretty town right out of a child’s toy chest. Prim little wood houses in yellow, pink and blue group neatly beside the water beneath mountain ranges that were still full of greenery and sunshine in the foreground but barren, misty, already snow-spotted in the background.

The moderator of my session, a representative of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, asked me if I minded speaking first. I said I’d prefer it that way; if Yevtushenko went first, the audience would disappear the moment he finished.

The moderator laughed. ‘That’s not the problem,’ he said. ‘If you don’t go first, you are likely not to get the chance to speak at all.’ He paused. ‘It is a little, er, difficult to stop him once he gets going.’

But there was no Yevtushenko in the theatre when the session started. A minute or two into my speech, a figure appeared in the front row. I’m no good at faces, but I was pretty sure this was the great poet because he stared at me in that disconcerting, unblinking way that Russians do. When I finished, the moderator thanked me — pointedly — for keeping to my 20-minute limit. A Dane spoke after me. When he finished, the moderator thanked him too — again pointedly — for keeping to the 20-minute limit.

Then Yevtushenko got up from the audience and made his way on stage. He wasn’t the man he had been, but then he was nearly 70. His hair was thin, his face deeply lined, his back no longer straight. Even so it was clear at once what all the fuss was about. This is a hell of a delivery. Maybe his English belongs in a farce, but no Western voice soars and swings like that. Up and down. Loud and soft. Face and body in motion too. He began with an unpublished poem and went on to something about a Russian nutcracker, Tschaikowsky’s swans and great big dinosaurs. But he could have been saying anything, anything at all. With a delivery like that, who cares?

He’s a man who knows how to handle a moderator too. After 40 minutes or so, he turned to ours (who was visibly restive) and said, ‘Is all right? I can finish? You permit?’ He didn’t sit down with the Dane and me until some 20 minutes later, and the moderator rushed in to take questions from the audience. The first one had barely begun when Yevtushenko leaned across to me. ‘What is phrase seel-kee prose?’ he said. ‘What this mean?’ In my speech, I’d described an American I knew as being master of the New Yorker’s ‘silky prose’. I explained as best I could. ‘Is good,’ he said. ‘Is little bit ironic, yes?’ I nodded. He leaned back in his chair, then forward again. ‘You sink?’

Sink? ‘I’m not sure what you mean,’ I said cautiously,

‘You sink?’ he said louder.

Could sink possibly mean think? Could Yevtushenko be saying I’d said something particularly stupid? Again I said, ‘I’m not sure what you mean.’

He leaned back in his chair. ‘You have beautiful voice. All seel-kee.’

Ah. Aha. Oh, my. ‘I’m afraid I can’t sing at all,’ I said.

‘Too bad.’ He turned to face the audience.

Dinner was on the top of the mountain overlooking Tromsø: a view out over mountain ranges and lakes below, rare reindeer meat and speeches. The writers were scheduled to read at a café after dinner and had to leave before dessert. As we got into the cable car to descend back to the town, a waitress handed out Sundae dishes with whipped cream on top so we could eat on the way. I found Yevtushenko beside me (it was a very small cable car); he looked at me curiously and said, ‘Why you eat ice cream?’

‘Didn’t you get any?’ He shook his head. ‘It isn’t ice cream. It’s a sort of custard. Very good. Want a taste?’

I spooned up a bite and fed it to him. A small bit of custard stayed behind on his cheek. God knows what possessed me, but I wiped that little bit of custard away with my fingers. ‘You have voice like ballet,’ he said softly, ‘Voice moves, rhythm. Beautiful.’

The café was quite large, perhaps 35 tables, perhaps more, dark, noisy, very full, very animated, the stage set up for the readings to come with microphones, spot-lights, pitcher of water, glasses. My agent and I sat near the back; the Irish ambassador got us drinks. Yevtushenko was sitting a table away, his back to us; as Helen Epstein of the United States started reading a grim passage about the holocaust, he swung around in his chair.

‘I show you poem,’ he said to me. ‘You read? Yes?’ He opened a paperback of his poems — English on the left hand page, Russian on the right — and turned to a pretty verse called Metamorphosis that described life in four stages through the names of Russian villages; they turn out to have very much the same feel and cadence to them as English villages. I mouthed the opening lines

Childhood is the village of Rosycheekly

Little Silly, Clamberingoverham …

‘No, no, no.’ he said. ‘Out loud.’

‘Out loud? Me?’

‘You read.’

‘Now?’

‘Out loud.’ I read the poem out to him, stumbling a little (I’m slightly dyslexic and those village names are a nightmare); he cued me at almost every phrase. ‘Stronger here. Sad here. Broken English is good for poems. But not this one. You read for me?’

‘On stage?’

‘Yes, yes. On stage.’ I hesitated. ‘I know. I know. Is difficult. I am professional. I help you.’

Amos Oz of Israel came on and began to read. Yevtushenko turned again to me.

‘You read another poem? Is okay? We do together. Line in English. Line in Russian. You understand?’ He took the book from me (I’d been trying madly to memorise the village names), found the page and handed it back:

I love you more than nature,

Because you are nature itself.

I love you more than freedom,

Because without you, freedom is prison…

And lots more of the same. Now I was once a pretty girl, but that was a long time ago. And this ancient poet was once a heart throb, but that was a long time ago too. Two old crocks saying things like this in front of an audience hardly seems dignified. I gave him a worried glance.

‘You have beautiful voice,’ he said with a shrug.

Well, what the hell, it was getting late, and I’d had too much wine. Besides I’d been in love once myself. ‘Okay,’ I said. ‘I can’t promise anything, but I’ll try.’

Joseph O’Connor of Ireland began to read. A stunning blonde woman just across from us caught Yevtushenko’s attention.

‘She look like Julie Cristie in Dr Zivago. Like Lara,’ he said to the Irish Ambassador and then leaned over to the blonde.

‘You married?’ he said.

‘Yes,’ she said.

‘Little bit married? All way married?’

‘All the way.’

‘You are perfect?’

‘No one is perfect.’

‘Ah. Good. I speak you later.’

He patted her shoulder, thought a moment, then turned back to me. ‘Another poem. We do together. Yes?’ He grinned impishly. ‘If they permit me have time.’

This one was called The City of Yes and the City of No. The City of No is a very dejected place. I could manage it just fine. It ends with the lines

No, no, no

No, no, no

No, no, no.

But the City of Yes is another affair altogether. Oh, dear. Here is a place where ‘Lips ask for yours without any shame … daisies ask to be plucked… herds offer their milk.’ It ends (as you might expect)

Yes, yes, yes

Yes, yes, yes

Yes, yes, yes.

An old crock blithering on about love is one thing, but this! I’d lived in England more than 30 years, and such things just … This time the glance I gave him was very worried.

‘You are born actress,’ he said. ‘You read.’

‘I’m afraid you’re going to be disappointed.’

‘Never.’

‘I just don’t think I can — ’

‘You do good. I know. You read. I want to hear.’

I felt like an idiot, but what else could I do? I gave those yes’s a try.

He shook his head. ‘Read like this,’ he said. ‘“Yee-eeees.” He looked at me achingly, longingly (a little over the top, but never mind): ‘ “Yeeee-eeees, yeeee-eeee-eeees”. Is orgasm: You understand?’

I’d been so excited at the honour of being invited to this affair that I’d forgotten to bring a copy of Theory of War with me, so when the time came for my reading, all I could do was give the gist of the story and listen while someone read from the Norwegian edition. I don’t know a single word of Norwegian. Besides, how could I keep my mind on that with Yevtushenko’s poetry session ahead of me?

When his turn came we went on stage together, Yevtushenko and me. I stood to one side while he began telling a little about his famous poem Babi Yar, how much official rage it had caused, how much fear, how his publisher had been sacked for printing it. Then he began to recite.

My husband used to say that we have fallen on passionless times. But it isn’t something I’d really understood until Yevtushenko spoke. Babi Yar itself carries a whallop; but with this powerful, flexible voice entreating, protesting, sorrowing, proclaiming, demanding — well, I’d say it’s the damndest performance I’ve ever been privileged to witness.

My part in the act, when we got to it, was definitely anti-climactic. I read the first verse in English about the village of Rosycheekly. He recited it in Russian. And for the first time I got some idea just why W.C.Fields put whiskey in Baby Le Roy’s milk. There was great good humour in the upstaging, but it was shameless. Face, gestures, body: all accompanied the voice that swung around its extraordinary spectrum like some souped-up car at a drag race. The audience laughed in delight.

Then came the love poem, and to my surprise he didn’t let go of the hammy, humorous style. Here we were, saying these things to each other — or that’s how it looked anyhow — and the audience was laughing happily, half with him, half at him, half enchanted, half embarrassed. He stroked my shoulders. He kissed my cheek. He pulled me into his arms. We ended on a triumphal note in that embrace, and he said to the audience:

‘Is good, yes? We have only one rehearsal. At table. Next time: Carnegie Hall.’

And we still had the City of No and the City of Yes ahead of us.

As I read about the City of No, he left the stage and started out into the audience. He went from table to table, leaning over the women — the men might as well have been dead — commiserating with them (the City of No is not a friendly place), eyeing the gorgeous blonde near our table but not approaching her.

Then — oh, dear Lord! — we got to the City of Yes. He turned into something out of whorehouse rock, any manner of sex for sale at any price. He prowled toward the blonde through the other women, kissing one en route, stroking another’s cheek, the voyeur-audience roaring with laughter around him, still embarrassed but mesmerised too.

As we hit our, uh, orgasm of ‘Yes, yes, yes’, he reached the blonde.

I didn’t see him after the café — I don’t know if his blonde spent the night with him (I do hope she did) — but as I was leaving my room the next morning I met him at the elevator.

He wore a pink golfer’s cap at a jaunty angle. ‘Why you not eat breakfast?’ he said with polite concern.

‘I had it in my room,’ I said.

‘Thank you for reading.’ He inclined his head in a formal bow.

I nodded in formal acknowledgement. ‘It was an honour.’

Before our performance, I’d told him he’d have to give me the book I was to read from. When we finished, he wrote in it for me, ‘To Joan Brady. To the woman with the silky voice’ — he’d paused then and beat out a rhythm — ‘and the golden soul.’

Before our performance, I’d told him he’d have to give me the book I was to read from. When we finished, he wrote in it for me, ‘To Joan Brady. To the woman with the silky voice’ — he’d paused then and beat out a rhythm — ‘and the golden soul.’

Maybe it’s not his finest line, but it’s certainly one for pride of place in the memory book.

Yevgeny Yevtushenko