Whitbread Book of the Year

From the Whitbread Press Release

FIRST EVER WOMAN TO WIN

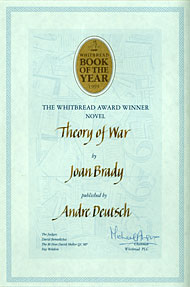

Whitbread Judge David Mellor MP QC said, ‘Theory of War is a fascinating book, part family history, part vivid act of re-creation… a searing account …you’ll never forget it.’

A fierce, elegant and violent novel … a passionate outcry against man’s most savage and terrible creation: the human character deformed…”

It all began very quietly. An announcement arrived at Andre Deutsch, publisher of my novel Theory of War. “Dear Publisher,” it said. “Congratulations on being short-listed for one of the 1993 Whitbread Awards” — exactly like the telephone recordings saying you’ve won the lottery — “The winners will be announced on 8 November.” Not promising. I was up for the Novel Award. Even less promising. I doubt that Deutsch had printed more than 2,000 copies of the book, and they hadn’t sold all of those.

And the other contenders for the Novel Award! My God! John Banville, William Boyd, Michael Ignatieff and Nigel Williams. All famous. All best-sellers. All men.

“Hopeless,” I decided.

There were five shortlists in all: Novel, a separate category for First Novel, Biography, Poetry and Children’s book. A winner was to be chosen in each category, and then the overall winner from these: “Best dog of show,” as somebody joked.

My agent told me that the shortlist winners would receive an invitation to lunch about a week before the official announcement. “When do the losers hear?” I said. He told me that they didn’t. They just didn’t get invited to lunch.

Less promising still. I tried — and failed — to put the whole thing out of mind.

Fleeing to New York in November seemed like a really good idea; that way, I’d escape the upset not getting an invitation. My agent, ever cautious, called the Whitbread people and asked them if I might be wise to postpone my trip. They said they’d certainly prefer it if I did. On the other hand, what else were they to say?

And yet to my astonishment, an invitation did arrive.

Lunch was in a big room at the Whitbread brewery. I sat with my agent and one of my judges, Fay Weldon, who turned out to be charming, funny, warm, reassuring. The ceremony is a blank in my mind. So is the food that followed it. So are the interviews, radio, television, newspapers. I got led — just as dazed — to a movie stars’ photo shoot with the other category winners: Andrew Motion, soon to become Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, soon to be awarded an OBE and then a CBE then follow Andrew as Poet Laureate, Ann Fine, the award-winning children’s author, and Rachel Cusk who was very young and very pretty — already well known for Saving Agnes, winner in the First Novel category.

The big prize-giving, Book of the Year Award itself, was scheduled for the end of January, nearly three months away. I remember lying in the bath night after night, knowing it was only a fluke that had got me this far — that there wasn’t a chance in hell that I’d go any further — and railing at the hopelessness of it. “At least,” I told myself, “I don’t have to compose one of those idiotic speeches.”

The Book of the Year is a very grand affair, and after Christmas, my agent said, “Joan, I think the time has come for a frock.” I hadn’t worn a skirt or heels in years. A friend in Dartmouth dressed me in her clothes, even down to an elegant coat; I bought a pair of high heels at Marks & Spencer. When I got them home, I realized they didn’t fit. I had to stuff the toes with cotton.

The night was a glittering affair of MPs, celebrities, top agents and heads of publishing companies. The dining room was vast and filled with large round tables. I sat with a number of people, including my agent and his wife, my editor Esther Whitby, Tom Rosenthal, the nominal head of Andre Deutsch, Laura Morris, the brains and energy behind him, and a reporter from the Guardian. We ate an elaborate dinner and drank a lot of wine while films were shown about us contenders and our books. The tension of such an occasion is terrible even if you’re certain, as I was, that your part in it is over. In an interval before the winner was to be announced,

Laura and I went for a pee, and if it hadn’t been for her — Well, I’d forgotten how tricky skirts can be, and mine had got tucked up in the top of my tights. I didn’t even notice, and if she hadn’t warned me, I’d have gone to collect my prize with a bare ass.

The over-large shoes hurt. Soon after we got back to the table, I bent under it to take them off while the winner was actually announced. After all, I knew who it was. We other contenders had all agreed among ourselves: there’d been a preponderance of men in the shortlists. Now there was only Andrew. Not just that. He was already very highly regarded and very well-known — good-looking too. He was also the bookies’ favorite.

I didn’t even hear my name. My agent had to fetch me out from under the table to tell me I’d won.

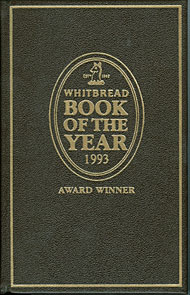

The steps to the winner’s dais were on different levels. I’d stuffed the cotton back into my shoes so fast that I’d got it in all the wrong places. The shoes wobbled. I wobbled. Fortunately David Mellor was holding my elbow, an unexpectedly warm man, unexpectedly likeable, very gentle. If he hadn’t been there, I’d have fallen on my face. Somebody handed me a leather bound volume of my book. I have no idea who. I stared out over that room full of important people — spotlights in my eyes — and wished with all my heart that I’d at least tried to work out something to say. All I could do was mumble about how shocked I was to be standing there, realizing even as the words were coming out of my mouth that every winner says that, and nobody believes a word of it. I know I thanked some people. But I’m so bad at names that I’m sure I didn’t thank the right ones.

At least the speech was short.

A couple of Whitbread staff members led me out to what looked like a camper van. One of them sat me down where the sink should be, told me this was where I’d do my radio interviews, then left me there. Very odd after all the commotion: talking to an empty kitchen sink like Cinderella after the ball.

The rest of the evening is as much of a daze as the Novel Award had been, but I ended up at home a few days later with a cheque for £21,000 in my hand.

Nothing’s been the same since.

to top Bound Book of the Year

Bound Book of the Year

Novel of the Year Plaque